S01E04 How's the water? - Complex & adaptive

Corporate blind spots, the limits of the clockwork worldview, a worldview update based on complex adaptive systems

In last week’s episode, it became clear that the clockwork logic is deeply ingrained in our work culture. Many people have accepted managerialism - the Taylorist top-down approach to management - as a fact of corporate life. That is if they even stop to wonder about the organizational design choices their companies have made.

Apparently, it’s not easy to recognize the mental models that govern us. David Foster Wallace makes the point beautifully in this brilliant commencement speech:

“There are two young fish swimming along who happen to meet an older fish. The older fish nods at them and says: ‘Morning boys, how’s the water?’ The two young fish swim on for a bit and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and asks: ‘What the hell is water?’”

— David Foster Wallace.

The point of the story is that the most obvious, important realities are often the hardest to see. One way to become aware of the water in which we swim is to question our assumptions and the foundational principles that lie beneath. This approach is known as first principles thinking.

What assumptions exist in organizational governance?

The best way to manage an organization is through top-down command and control.

Control happens on the functional level: an IT manager oversees the IT people, a marketing manager oversees the marketing people, etc…

Management and planning are separate from operations and execution.

In the first episodes, I proposed that these assumptions are themselves rooted in the clockwork worldview of Modernism. Building on Newtonian mechanics and the discoveries of the scientific revolution, humanity had become confident in its ability to understand, control, and predict how the world works.

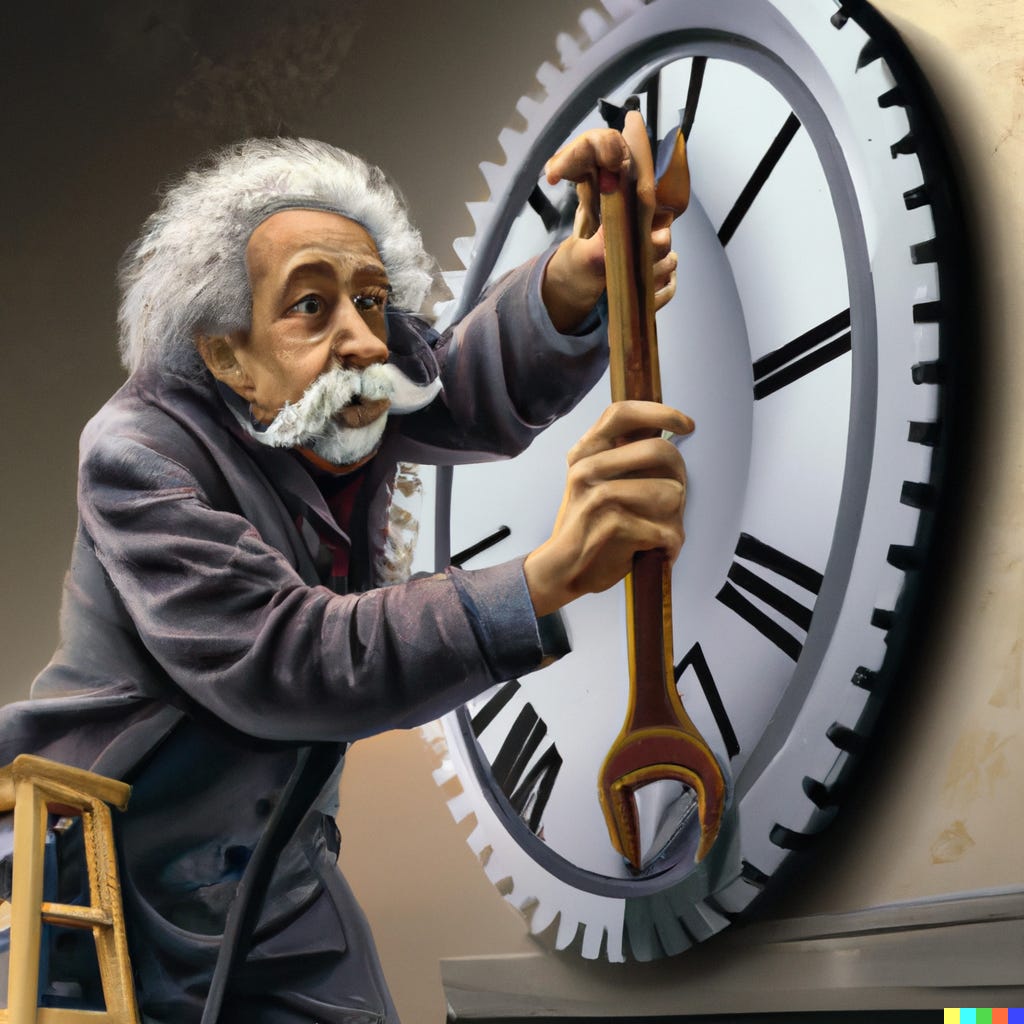

A quantum wrench in the clockwork

Newton was not wrong. In fact, we still rely on his theory of gravity to predict the motion of celestial bodies. The problem with the clockwork approach is that Newton’s mechanistic contributions explain some of the dynamics of our universe, but not all of them.

At the beginning of the 20th century, scientists like Planck, Einstein, and Heisenberg shone a new light on the physical laws that govern how objects move. Newtonian mechanics helped explain the movement of macroscopic bodies, while the newly-discovered quantum mechanics described the behavior of microscopic bodies such as atoms and subatomic particles.

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle is an important theory behind quantum mechanics. It states that you cannot measure a particle's momentum and position at the same time. This principle disproves Laplace’s demon: the idea that a super-mind could predict the future if it knew the speed and position of all the particles in the universe.

With that, the central tenet of the modernist worldview had been invalidated. The idea that the state of the universe at one time determines the state at all other times, turned out to be wrong.

Although the modernist worldview had lost its scientific footing, this did not immediately discredit the other ideas that had been built on the foundations of reductionism, linearity, and determinism.

Take Taylor’s clockwork approach to corporate governance; managers have grown quite comfortable cultivating the illusion of certainty. On Microsoft Teams, no one is in a hurry to question any foundational beliefs.

It took us half a millennium to replace the religious worldview with the modernist approach - and religion is still here. Similarly, the quantum update will take time to propagate through human operating systems (although technology might accelerate things this time around).

The main thesis of Season one is that most managerial and organizational practices are deprecated; they are grounded in a worldview that comes with a misplaced sense of deterministic control. We need a new way to make sense of the world we live in. Before we circle back to organizational practices, I want to offer another model of the world, one based on complex, adaptive systems.

From clockwork to complex, adaptive systems

It turns out that an alternative to the clockwork worldview has been staring us in the face all along. Nature offers us plenty of examples: flocks of birds, the weather, our immune system, forests, the human body… All these systems exhibit behaviors that cannot be predicted from their components. Intuitively we know that the clockwork metaphor breaks down at this point.

Of course, I need more than intuition if I am to frame complexity as a basis for a new worldview. What does science have to say about complex systems? For now, there is no single science of complexity nor even an established definition. The field is fairly young and has its roots in different disciplines and domains.

Absent a definition; the next episodes will look at complexity from different angles. Reassuringly, complex adaptive systems play a role in many scientific disciplines, both hard and soft. With such an abstract subject, it’s easy to get bogged down in theory, but I’ll take care to punctuate the story with examples.

Perhaps the most striking illustration of a complex, adaptive system is a colony of ants. The colony as a whole is capable of incredibly sophisticated feats of engineering. Ant nests make smart use of materials to create networks of underground passages and even regulate their brooding quarters' temperature. Colonies construct living bridges for different evolutionary purposes (scaffolding, defense mechanisms, predatory behavior…).

How ants accomplish this, is radically different from the clockwork approach to organizing and building. Consider how a living bridge compares to its mechanistic, man-made counterpart:

“Bridges and buildings are all designed to be indifferent to their environment, to withstand fluctuations, not to adapt to them. The best bridge is one that just stands there, whatever the weather.”

— Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain.

Emerging, organic bridges, on the other hand, interact with their environment and become a part of it. They are the result of self-organization instead of central planning. Individual ants are equipped with minimal cognitive resources, and there are no colony architects or project manager ants to oversee the proceedings.

Biologists have known and studied this complex group behavior for a long time. A more recent evolution is that scientists have started to look for similar patterns in other fields. That is the scope of the emerging field of complexity theory. A logical place for researchers to start was to look for common properties among complex systems.

The modernist worldview was built on determinism, linearity, and reductionism. What are the foundational principles and common characteristics of complex systems? And do they constitute a better model of the world? Tune in next episode for more nerdiness.

looking forward to the next episode, I like particular the ant story