S01E03 How the world changed after Taylor: everything-as-a-service

How the information revolution changed value creation, everything-as-as-service, malicious effects of separating thinking from doing

Although Frederick Taylor is no longer a household name, he is still well-known among scholars of economic and military theory. If the US hadn’t been the manufacturing powerhouse that Taylor helped create, World War II might have ended very differently.

One of the most influential thinkers on management theory, Peter Drucker, said that Taylor should have his place alongside Freud and Darwin in the trinity of ‘makers of the modern world’ (taking Marx’s place). In his book Post-Capitalist Society, he later added:

“Frederick W. Taylor was the first man in recorded history who deemed work deserving of systematic observation and study. On Taylor's 'scientific management' rests, above all, the tremendous surge of affluence in the last seventy-five years which has lifted the working masses in the developed countries well above any level recorded before, even for the well-to-do. Taylor, though the Isaac Newton (or perhaps the Archimedes) of the science of work, laid only first foundations, however. Not much has been added to them since – even though he has been dead all of sixty years.”

— Peter Drucker, Post-Capitalist Society.

Drucker emphasized the importance of Taylor’s contributions in 1993. At that time the Internet looked like this:

The gap between management theory and the reality of work in the information age has only widened since then. To Drucker, I would say that we should not only add to the body of work that Taylor founded, but we should first trim the parts that are no longer valid.

Clearly, the world of the information era is far-removed from Taylor’s industrial production lines. For one, creating software is more akin to inventing than it is to manufacturing. Because it is a creative process, there is no One Best Way to do something. Entrepreneur and investor Chris Dixon described software as “the encoding of human thought.” In other words, the design space of software is literally limitless.

On the demand side, consumer needs are equally unlimited. Technology has enabled a shift to a services economy where people value access, customization, and experience over ownership. We went from CDs and DVDs to streaming platforms, and from grocery shopping to meal kit delivery. Even traditional products like cars are starting to offer subscription services and over-the-air updates of the product. Enterprises are moving from on-premise computing and heavy capital assets to the cloud and towards asset-light operating models.

The traditional organizational approach was centered around production: churning out high volumes of product with a focus on efficiency and standardization. This approach breaks down in a service context. When you introduce customers into operations - the very definition of a service - you add complexity. And complexity defies standardization.

An organization that wants to succeed in the information era needs to continuously listen, adapt, and respond. All services exist by the grace of co-creation with their recipients. Over-the-air updates and the Internet have changed the rules of this game; companies can react more quickly to user feedback, and consumers are increasingly expecting them to do so.

This creates all sorts of problems for non-Internet-native organizations. They still operate under the Taylorist assumption that planning should live separately from doing. Everything about them has been optimized to mass-market a one-way flow of materials and resources. This modernist worldview is so deeply ingrained in their organizational system that it is hard to recognize, let alone root out.

Spreadsheet-wielding managers persist in their planning monopoly for a world they expect to be predictable, no matter how often their reductionist, linear, and deterministic approach was proven wrong. In an attempt to regain control, they analyze and adjust components without considering that the whole may be more than the sum of the parts.

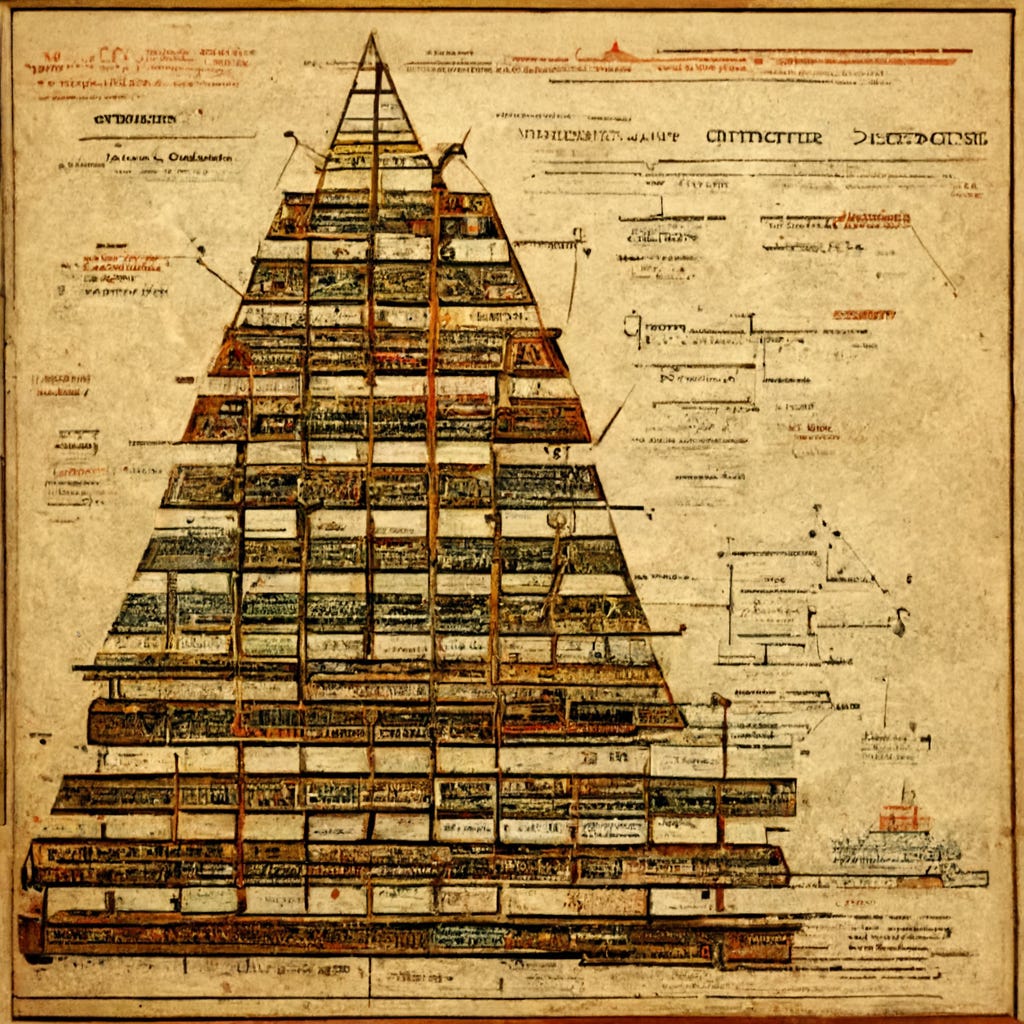

The archetypical mechanistic org is shaped like a pyramid. It has vertical departments for functional specialization and horizontal tiers that depict hierarchy levels. Power is concentrated at the top, where strategic decision-making happens. Much of the control function resides with middle management. They translate the leadership’s vision into discrete tasks and hand these down to the workers, who take direction without much impact on the planning and decision-making layers.

As traditional companies scale, communication between departments is funneled through middle managers, endowing them with a gatekeeper’s ability to filter information flows upwards, sidewards, and downwards. When that happens, organizations lose the network characteristics they took for granted when they were smaller. Often they will start to function as bureaucratic oligarchies, where policy is driven by company politics instead of the best interest of customers and employees.

All these patterns extend from the foundational belief that planning and execution should be separated. These segregational tactics may have worked in an industrial context, but tend to backfire in a digital context. Decoupling execution from decision-making is sure to dishearten any 21st-century humans being served by the system, whether as customers or as employees.

In the next episode, I’ll introduce the complexity worldview that may offer a way out of Modernism.

Further reading

Jeff Gothelf & Josh Seiden, Sense & respond