S02E06: Career cartography

Netlog Mafia, one-on-ones, alignment without the cringe bits, ikigai but with company constraints, vector maps, career/company fit

Last week, the 'Netlog Mafia' gathered for a reunion party. For those outside Belgian tech circles, that's our version of the PayPal Mafia - the network of entrepreneurs who spun out of the social network that put Ghent on the startup map.

The event, combined with recent acquisition buzz around companies like Showpad (whose co-founders met at Netlog), had everyone talking about how Ghent punches above its weight in European tech.

For leaders, this concentration of ambition creates an interesting challenge: how do you keep great people engaged when they're surrounded by other fast-growing startups doing fascinating work? It's a good problem to have, but still something to solve.

This brought me back to the question I ended with in my last essay: given that any company consists of people with wildly varying quirks, needs and career ambitions, how do you get them to act in concert with the company's needs? And how do you keep talent engaged through the inevitable rough patches?

How (Not) To Talk To People At Work

I already know what doesn’t work. When I coach people who oversee teams, I like to ask them how they engage team members in individual conversations. If their one-on-ones read like a laundry list of hoops to jump through, I know I will find blind spots in their team.

Some managers ask okayish questions - “Where do you see yourself in a few years?” “What motivates you?” - but these land flat if they come across as scripted. Good conversations flow both ways. That’s easy to forget in hierarchical settings, where people take turns performing.

Most companies treat career conversations as performance theater, but they're actually your best early warning system.

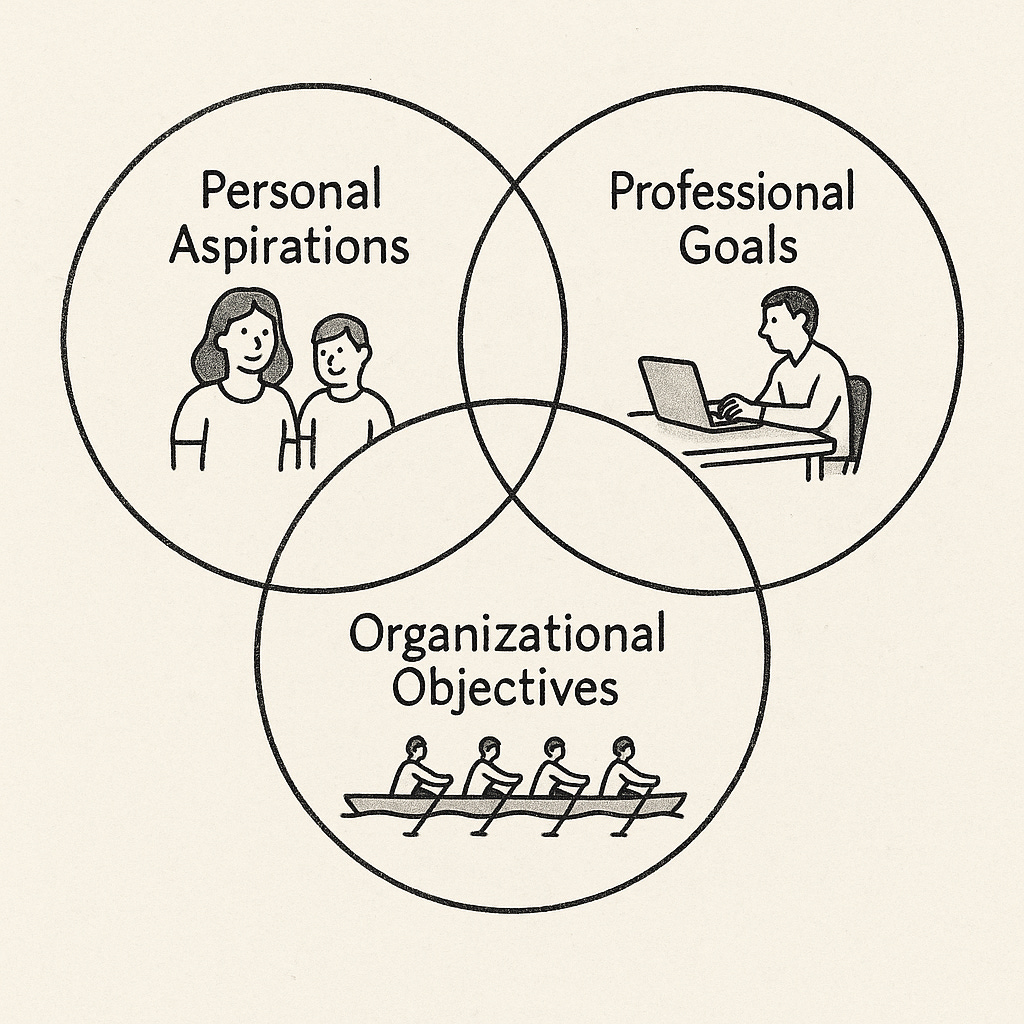

I want to share with you a model for approaching conversations around career perspectives. For you to steal or give feedback on. It’s not a very fancy model. It’s just a Venn diagram if I’m being honest. But I find it helpful.

The Career Vector Map

Imagine three overlapping circles:

Personal aspirations: who you want to become, how and where you want to live. The stuff we pretend doesn’t matter at work, until people quit because of it.

Professional goals: what you expect from your career, what skills you want to build, what roles you’re aiming for… This is about mastery, leverage, and identity.

Organizational objectives: what the company needs, bets it’s making, roles it’s willing to back. This is about how leaders translate vision slideware to reality.

I know 'navigating alignment' sounds like the kind of phrase that gets thrown around in recurring meetings by people who’ve not done any real work since Y2K. But strip away the jargon and that's genuinely what I'm trying to map; the literal geometry of someone's working life.

The default assumption is that alignment “just happens.” That if someone’s doing their job and getting paid, the rest falls into place. Things are rarely so simple. People and companies evolve, and their vectors fall in and out of alignment constantly.

The point of this model is to make these shifts visible. It gives people a shared surface to talk about what usually stays vague. Sometimes I actually draw the circles on a whiteboard, sometimes it stays a mental exercise. More often than not, it’s what gets the conversation off the corporate rails and into the terrain that matters.

The Permutations Are The Point

I forgive you for assuming that the goal is to get all three circles to overlap. A perfect bullseye is rare, temporary, and not always necessary.

The entrepreneurial employee

Imagine, if you will, an exceptional performer: hard-working, high-agency and passionate. How do you retain people like that? The trick is to understand what makes them tick.

People like this often dream about founding their own venture, and they may see the current engagement as training wheels. This arrangement can be mutually beneficial, even if it’s only temporary.

But you can dig deeper. How sure are they about becoming a founder? If they have what it takes, you won’t be able to stop them but the path is not for everybody... There’s a middle ground between employees and founders; tools like ESOP’s, when used wisely, allow companies to offer people a combination of skin-in-the-game and a degree of certainty about their income.

The well-liked misfit

Here’s another persona: cultural glue, morale booster, maybe part of the early team. But the role has outgrown them. Everyone avoids the topic because it feels personal.

The goal of the diagram is to make it clear when a person’s trajectories and organizational needs diverge. This helps make it not personal. It lets you talk about the delta without making it a judgment.

Then the question becomes: is there a role for someone whose professional goals aren’t evolving, but whose presence still adds value? Sometimes the answer is yes. Sometimes it’s time to say goodbye.

The fast burner

Every company has people like this: driven, ambitious, and technically sharp, but always looking for the fast track of career development. They want a leadership role, but the company’s not ready. Or they want to switch domains, but there is no vacancy in the new domain.

This is where good leaders earn their keep. They don’t say “no”, but they say things like: “not yet”, or “not here, but there”, or “not until you demonstrate your capabilities on thing X”. By definition, individual contributors have less of a bird’s eye view, and they can use help calibrating their ambitions with the available options.

These examples show how the map works for individual conversations. What most companies miss, is how these conversations should shape the system itself.

From Performance Reviews to Learning Loops

In all but the best companies, career conversations are framed like evaluations. Managers ask firm questions about progress toward goals. Employees answer. The result is a pat on the back or a warning to do better. Corporate-sponsored performance theater.

In the best companies, leadership revolves around engaging in real talk with the people in the trenches. When people tell you which interactions / processes / partners sap the joy out of their work, that’s valuable data.

Departments that ooze drama, domains that can’t seem to grow leaders, individual contributors who can predict project failures before the first letter of code is written… These are early signals that show up in people’s stories long before they show up in metrics.

Most orgs don’t have a way to catch those signals. Managers aren’t trained (or incentivized) to listen systemically. When these stories don’t even surface in private 1:1s, there’s no way to act on them.

The take-away then is to treat career conversations as a bidirectional learning loop, with the map on the table and curiosity on both sides. People should be able to take feedback, but also to dish it out.

In learning organizations, it’s the prerogative of the people in the trenches to call out their leaders on the effectiveness of their strategies and tactics. True leaders acknowledge and embrace this two-way street.

Of course, this leadership style does not work in isolation. If you want people managers with the mandate to relay messages upward, downward, and sideways, the entire organization needs to be receptive to this feedback culture.

Final Thoughts

This model is messy by design. It doesn’t spit out decisions. It requires leaders that can juggle multiple perspectives simultaneously. The pay-off is it can bring humanity back into systems that too often try to abstract people away.

Disclaimers:

I am a proud member of the Netlog Mafia myself and I have a vested interest in propagating this brand 😎

AI slop is taking over the Internet (“It’s not this — it’s that”). I appreciate LLMs as a tool to sharpen ideas; but I can promise my readers that I still do my own writing.

Here is a good essay on how to use AI without becoming stupid.